Trudging through an early December snow storm in Washington, D.C., a few weeks ago, after a chilly ten-minute walk, Tyler and I finally spotted our destination: the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery. After visiting friends and colleagues at Colonial Williamsburg, we stopped in D.C. specifically to see the exhibition Murder is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, organized by curator Nora Atkinson.

What’s the story?

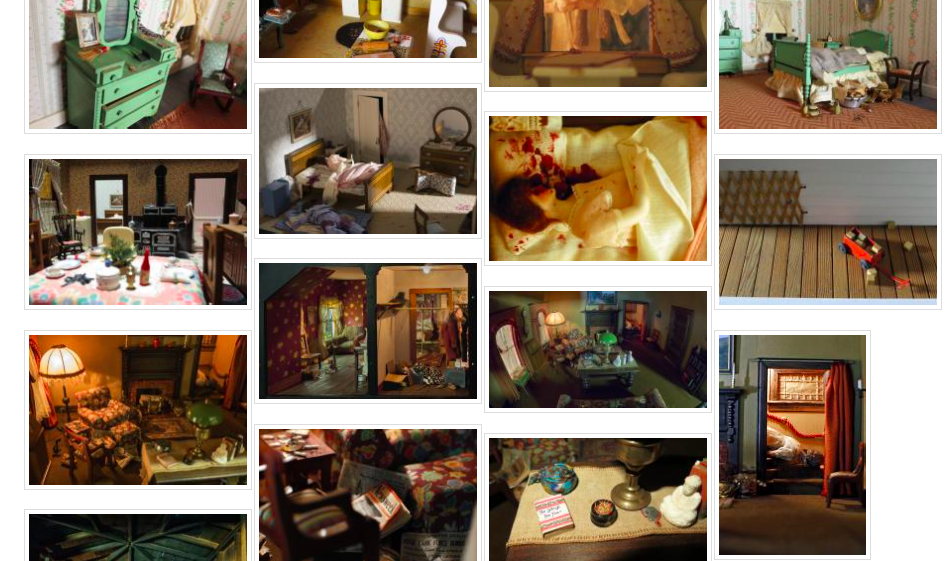

In the 1940s and 50s, Lee (1878-1962), considered one of the founders of forensic investigation, created these didactic dioramas (with a partner who did a lot of the carpentry) based on real crimes for the purposes of training budding police and crime investigators in Harvard’s now defunct department of Legal Medicine. In 1966, Harvard transferred the nutshells to the Maryland Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, where they are still in use today for training purposes. These studies are, as Lee put it and as Atkinson explains in this video, about “finding truth in a nutshell.” This is not the first time these dioramas have been on display. See, for example, this 2008 exhibition at the National Library of Medicine, Visible Proofs: Forensic Views of the Body.

I like dioramas, I study medical history, and I learned about how New Castle County, DE, police get trained to investigate crime scenes when I participated in their citizen’s police academy a few years ago. I wanted to know more about the history of all this. But upon feeling the warm air on our faces as we walked up the stairs and edged toward the gallery at left, I stopped. All I could hear was the din of what I presumed to be a group that had rented the galleries for a private event. Museums make a lot of money from space rentals and I do not begrudge them this income stream. Still, a disappointment. Would we be unable to see the nutshell studies after all?

As my eyes adjusted to the dim gallery lighting, I quickly realized that we did not catch the Renwick at a bad time. We caught the Renwick at a good time. The noise, which sounded like the soundtrack of a popular bar, was, in fact, emanating from the exhibition visitors. Tyler and I observed in awe as one group of strangers exchanged theories and practiced a whole lot of close looking at the supposedly best known nutshell study that depicts an entire home and multiple “unexplained” deaths. The crowd did not clear while we were there, and so we never got to look at this particular nutshell (see below).

“This is what museums and public history should be about,” I murmured to Tyler, also a museum person. “But how often do you actually see this happening? Discussion, laughter, awe, wonder, questioning.” Tyler nodded and took a few surreptitious photos and a short video (for teaching purposes!).

This experience increased my expectations for public historians. We need to create similarly thought-provoking exhibitions and programming, even when we are not beginning with what we might argue to be inherently extraordinary material culture (you know, mummies, diamonds, airplanes, miniature recreations of murder scenes, and the like). Not sometimes. Every time.

This experience also got me to rethink how I talk to my students about museum etiquette. If you had asked me how to behave in a museum prior to going to this exhibition, I would have noted that talking is OK but that it should be kept to a minimum. Indeed, I have instructed my students to behave this way in my “history behind the scenes” course when they are in traditional gallery-style museums. That’s what I learned growing up frequenting museums and historic sites, and I think that is still a widely held expectation among visitors.

But does it always need to be that way?

Of course not, but it took this visit to the Renwick for me to come to that realization. Many of us in the field are rethinking the way we engage with the public in history settings. I could cite a lot of folks here, but I’ll only note Vagnone’s and Ryan’s Anarchist’s Guide to Historic House Museums (2016) even though they use house museums as opposed to traditional galleries as a case study. In short, they argue, we need to make historic house museums “more relatable” (pg 39).

What is our role in facilitating this?

As our experience at the Renwick shows and as Steven Lubar noted in his new book Inside the Lost Museum: Curating, Past and Present (Harvard, 2017), “Museums are more than just places with things: they are places with things and people, that is, social spaces” (pg. 157). We need to keep this in mind when we curate exhibitions, design public programming, advocate for our field’s relevancy, and instruct our students in museum etiquette. You will know we have been successful if the next time you go to an exhibition or public history event, you, too, think that you have walked into a bar.

For more on the exhibition see, for example this article published by Harvard Medical School.

You can also learn more from this Smithsonian podcast with the curator.

Do you like documentaries? Check out this 2011 film, Of Dolls and Murder, which is about the Nutshells.

If you want to learn more about some contemporaneous dioramas, see the Thorne Miniature Rooms at the Art Institute of Chicago.

For those of you interested in the history of forensic science, see the online version of the 2008 U.S. National Library of Medicine Exhibition Visible Proofs: Forensic Views of the Body.

And finally, if you want to know more about the history of “hobbies,” Steven M. Gelber’s 1999 book Hobbies: Leisure and the Culture of Work in America, is a good place to start.